Every day, your cells run on a clock. And that rhythm may determine when you should take an NAD⁺ booster.

NAD⁺ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) drives the machinery of performance. It fuels the mitochondria that help turn nutrients into ATP — the current behind physical power, mental acuity, and sheer resilience. The higher your NAD⁺, the more efficiently your cells can sustain output and bounce back from strain.

But NAD⁺ doesn’t stay constant. Its levels fluctuate across the day, governed by the same circadian rhythm that regulates sleep and metabolism. In other words, NAD⁺ operates on a schedule, just like you do.

And that means what time you take your NAD⁺ supplement — morning or night — could influence how your body uses it.

In this article, we’ll explore:

How NAD⁺ boosters like nicotinamide riboside (NR) interact with your body’s internal clock.

Why timing could amplify their effects on energy metabolism and cellular repair.

And how combining NAD⁺ supplements with caffeine might strengthen that morning signal for both physical and mental performance.

What Is NAD⁺ and Why Does It Decline With Age

Everything you do runs on energy. Every step, every heartbeat, even every thought that sparks across your mind draws from the same cellular current. In a real sense, who you are depends on how efficiently your cells make and manage that power.

At the center of that process is NAD⁺, the molecule that enables mitochondria to turn nutrients into ATP, the body’s spendable form of power. When it is abundant, the system runs smoothly, letting us perform at our very best [1].

Over time, though, the supply dwindles. Once you’ve hit middle age, NAD⁺ levels in many tissues have fallen by roughly half [2].

And as NAD⁺ declines, mitochondria start to lag. By age 80, muscle cells may produce only about half as much ATP as they did in youth [3], while neurons lose roughly a third of their power output [4].

For decades, scientists thought this was just part of the steady attrition of age.

Then, in 2013, came a surprise.

When researchers restored NAD⁺ in old mice, their mitochondria snapped back to youthful performance within a week. The cells produced energy like they were young again [5]. What had looked like inexorable decay was actually a reversible slowdown.

So what causes this drop in the first place?

One major player is nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the enzyme that controls how quickly cells recycle NAD⁺ through the salvage pathway. It’s the rate-limiting step, the point that decides how much new NAD⁺ can be made from what’s already inside the cell. As we get older, it wanes, slowing NAD⁺ renewal and narrowing the cell’s energy margin [6].

But NAMPT activity doesn’t just fade over decades. It oscillates by the hour, rising and falling in sync with the body’s internal clock. Which means one thing: when it comes to boosting NAD⁺, timing may be critical.

The Body’s Clock and the Rhythm of NAD⁺

Every living system runs on rhythm. From the flicker of a neuron to the bloom of a flower, life moves through a ~24-hour cycle, all tuned to light and dark.

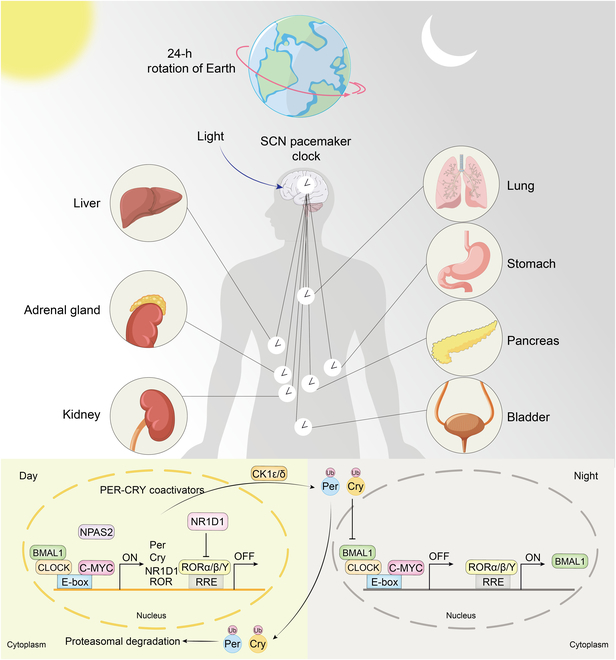

In humans, the master rhythm originates in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), a tiny cluster of neurons in the hypothalamus that receives light and dark signals through the eyes. In response to these cues, the SCN sends signals that reverberate outward to every tissue, syncing peripheral clocks so physiology stays coordinated [7].

Every organ — liver, muscle, gut, fat — keeps its own beat. When those rhythms move in harmony, metabolism runs cleanly: energy is made when it’s needed and conserved when it’s not.

That rhythm plays out inside every cell. Two proteins, CLOCK and BMAL1, act like molecular metronomes, switching genes on and off to match the body’s internal day [8].

Figure 2. Reproduced from J. Wang et al., Res. 8 (2025) 0612. DOI:10.34133/research.0612. CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2. Reproduced from J. Wang et al., Res. 8 (2025) 0612. DOI:10.34133/research.0612. CC BY 4.0.

One of their key targets is NAMPT, that bottleneck enzyme that determines how much NAD⁺ a cell can rebuild [9].

During the day, when energy demand is high, CLOCK and BMAL1 crank up NAMPT, accelerating NAD⁺ production. Computational models of this cycle suggest that NAD⁺ levels can swing by roughly 40% over each 24-hour period, peaking several hours after NAMPT expression [10]. Then, as the body winds down, NAMPT slows, NAD⁺ levels ebb, and cells pivot from energy output to repair [11]. The result is an internal tide: NAD⁺ rising with wakefulness, receding with rest.†

This rhythm shapes many body systems. For example, older adults who receive a flu vaccine in the morning mount a stronger antibody response than those vaccinated in the afternoon.

Why? Immune cells are more active early in the day. Mitochondria in those immune cells are primed for antigen processing, and the lymphoid system is more receptive to new signals in that window [12].

For NAD⁺ boosting, the same principle applies. NAD+ production appears to naturally peak during the body’s active window, when energy demand and mitochondrial output are highest.††

Furthermore, precursors don’t hit the bloodstream right away. They work in stages — absorbed, metabolized, and finally reshaped by your gut microbes — so their effects unfold over several hours [13].

Because of the lag time, it’s probably best to take NAD⁺ precursors in the morning, or soon after waking. Doing so lets you catch the system at its metabolic high tide, when your body is primed to produce and recycle NAD⁺ most efficiently.

And external cues that strengthen that daytime rhythm can push it even further.

Caffeine and NAD⁺: A Synergistic Morning Boost

Caffeine is the world’s most trusted performance enhancer. It works its magic by blocking adenosine, the molecule that builds pressure for sleep in the brain. When caffeine steps in, that signal goes quiet.

In circadian terms, caffeine functions as a zeitgeber — a cue that tells your cells that the day has begun, reinforcing the rhythm that naturally drives rising NAD⁺ in the early hours.

But caffeine’s influence extends beyond its stimulant edge. Inside muscle, it acts as a subtle metabolic signal by activating AMPK, the enzyme that senses when energy is running low and pushes the cell to make more [14]. Once switched on, AMPK signals the cell to make more mitochondria and recycle energy more efficiently. It also turns up production of NAMPT, resulting in greater NAD⁺ turnover and a faster metabolic response [15].

That same synergy extends to the brain, driven by another key molecular player: nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT), the enzyme that completes the salvage pathway by converting NMN into NAD⁺ [16].

In an in-vitro study using human cells, researchers found that combining nicotinamide riboside (NR) — a direct NAD⁺ precursor — with caffeine produced a bigger boost in NAD⁺ than either compound alone. The dual treatment did so by upregulating NMNAT2, the neuron-specific form of the enzyme [17].

The strongest response came from neural progenitor cells (NPCs), the stem-like precursors that generate new neurons and glia. Within 24 hours, NAD⁺ in these cells rebounded to near-youthful levels, even in samples from older adults with sluggish NAD⁺ metabolism.

Mechanistically, it’s a clean division of labor: NR supplies the substrate, and caffeine primes the machinery.

When to Take NAD⁺ Boosters: Timing for Maximum Effect

The data tell a clear story: biology runs on time.

NAD⁺ production naturally crests in the morning — the body’s biological “on” switch — and declines as night approaches. To get the most from your supplement, work with that rhythm instead of against it.

1. Take NAD⁺ boosters in the morning.

Morning is when your internal clocks, mitochondria, and metabolism are already aligned for energy output. Taking NAD⁺ during this window supports synthesis while your cells are wired to make and use it most efficiently.*

2. Pair it with caffeine.

Caffeine is both an activator and a signal. It primes NAD⁺ synthesis by turning on AMPK and NAMPT, while also reinforcing the body’s wake-phase rhythm.

3. Bonus: Add movement.

A morning walk or workout amplifies these same pathways. Physical activity activates AMPK — the same cellular fuel sensor caffeine triggers — further enhancing NAD⁺ turnover and mitochondrial renewal. It’s a simple way to make your morning stack work harder for you.*

Together, these cues — daylight, caffeine, and activity — create a kind of metabolic synchrony, signaling to every cell that it’s time to perform.

But when it comes to NAD⁺, timing isn’t the only thing that matters. Formulation does too.

The Smarter Stack: How Qualia NAD⁺ Maximizes Results

Qualia NAD⁺ was designed to work with your biology, not around it. It combines three complementary precursors — NIAGEN® (nicotinamide riboside), niacin, and niacinamide — ensuring that different tissues have access to the substrates they prefer for NAD⁺ synthesis.*

Rebuilding NAD⁺ isn’t just about providing the building blocks though. It’s also about supporting the cellular work required to convert, recycle, and sustain them. Qualia NAD⁺ includes a network of compounds that assist in this process: Coffeeberry® caffeine to activate NAMPT, resveratrol to stimulate NAD⁺ salvage and sirtuin pathways, and magnesium to drive ATP-dependent reactions.*

And this isn’t just mechanistic speculation — we’ve put it to the test.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, participants taking Qualia NAD⁺ raised their NAD⁺ by an average of 67% in just four weeks.*‡

By combining multiple NAD⁺ precursors with caffeine and key metabolic cofactors, Qualia NAD⁺ delivers what biology predicts — a smarter, more complete way to replenish the body’s energy currency and support performance when it counts most.*

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

‡Based on double-blind placebo-controlled studies. Individual results may vary. Full study results available at qualialife.com/nad-clinical2.

†Aging flattens these circadian oscillations, which may help explain the drop in NAMPT expression — as well as the corresponding decline in NAD⁺ production — with age.

††Some studies have not demonstrated strong circadian effects for NAD⁺ in specific tissues. For instance, one human study failed to find a significant difference between morning and afternoon NAD⁺ in the occipital lobe [18].

References

[1] E. Katsyuba, M. Romani, D. Hofer, J. Auwerx, Nat. Metab. 2 (2020) 9–31.

[2] J. Clement, M. Wong, A. Poljak, P. Sachdev, N. Braidy, Rejuvenation Res. 22 (2019) 121–130.

[3] K.E. Conley, S.A. Jubrias, P.C. Esselman, J. Physiol. 526 (2000) 203–210.

[4] F. Boumezbeur, G.F. Mason, R.A. de Graaf, K.L. Behar, G.W. Cline, G.I. Shulman, D.L. Rothman, K.F. Petersen, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30 (2010) 211–221.

[5] A.P. Gomes, N.L. Price, A.J. Ling, J.J. Moslehi, M.K. Montgomery, L. Rajman, J.P. White, J.S. Teodoro, C.D. Wrann, B.P. Hubbard, E.M. Mercken, C.M. Palmeira, R. de Cabo, A.P. Rolo, N. Turner, E.L. Bell, D.A. Sinclair, Cell 155 (2013) 1624–1638.

[6] J. Yoshino, K.F. Mills, M.J. Yoon, S. Imai, Cell Metab. 14 (2011) 528–536.

[7] C. Dibner, U. Schibler, U. Albrecht, Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72 (2010) 517–549.

[8] S. Imai, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804 (2010) 1584–1590.

[9] K.M. Ramsey, J. Yoshino, C.S. Brace, D. Abrassart, Y. Kobayashi, B. Marcheva, H.K. Hong, J.L. Chong, E.D. Buhr, C. Lee, J.S. Takahashi, S. Imai, J. Bass, Science 324 (2009) 651–654.

[10] A. Luna, G.B. McFadden, M.I. Aladjem, K.W. Kohn, PLoS Comput. Biol. 11 (2015) e1004144.

[11] S. Imai, L. Guarente, Trends Cell Biol. 24 (2014) 464–471.

[12] J.E. Long, M.T. Drayson, A.E. Taylor, K.M. Toellner, J.M. Lord, A.C. Phillips, Vaccine 34 (2016) 2679–2685.

[13] C.O. Otasowie, R. Tanner, D.W. Ray, J.M. Austyn, B.J. Coventry, Front. Immunol. 13 (2022) 977525.

[14] C. Cantó, Metabolites 12 (2022) 630.

[15] T. Egawa, T. Hamada, N. Kameda, K. Karaike, X. Ma, S. Masuda, N. Iwanaka, T. Hayashi, Metabolism 58 (2009) 1609–1617.

[16] X. Han, H. Tai, X. Wang, Z. Wang, J. Zhou, X. Wei, Y. Ding, H. Gong, C. Mo, J. Zhang, J. Qin, Y. Ma, N. Huang, R. Xiang, H. Xiao, Aging Cell 15 (2016) 416–427.

[17] I. D’Angelo, N. Raffaelli, V. Dabusti, T. Lorenzi, G. Magni, M. Rizzi, Structure 8 (2000) 993–1004.

[18] W.I. Ryu, M. Shen, Y. Lee, R.A. Healy, M.K. Bormann, B.M. Cohen, K.C. Sonntag, Aging Cell 21 (2022) e13658.

[19] B. Cuenoud, Z. Huang, M. Hartweg, M. Widmaier, S. Lim, D. Wenz, L. Xin, Front. Physiol. 14 (2023) 1285776.

No Comments Yet

Sign in or Register to Comment