The human brain is remarkable not because it is stable, but because it is changeable. Its networks are in constant motion — strengthening some connections, pruning others — a process known as neuroplasticity. This is what allows us to learn new skills, commit experiences to memory, and adapt to whatever life throws our way.

Yet neuroplasticity is not guaranteed. The same machinery that engraves experience into memory can, under the wrong conditions, start to work against itself. When signals lose their selectivity, the brain doesn’t learn more — it absorbs noise.

That fine balance comes down to chemistry. Plasticity depends on molecular gates that must open and close at just the right time. If they swing too wide, circuits grow unstable. Rather than refining connections, the brain amplifies background chatter.

This is where magnesium enters the story. It acts like a natural filter: keeping the gates closed to random static, while letting them open when the timing is right. This mechanism is part of magnesium's central role in brain health.

But its influence doesn’t stop there.

In this article, we’ll explore how magnesium supports brain neuroplasticity through three intertwined roles: keeping learning selective, amplifying growth, and protecting circuits under pressure.*

Just as important, we’ll look at what happens to brain power when magnesium is scarce, and why the form and context in which we get it may matter as much as the amount.*

What is Neuroplasticity and Why Magnesium Matters

Our brain rewires itself constantly in response to new challenges. This remodeling reshapes the architecture of the brain itself.

For instance, in one experiment, adults who learned to juggle for three months didn’t just get better at tossing balls. MRI scans revealed growth of gray matter in regions that track moving objects — physical changes laid down through practice [1].

Years of training can engrave adaptations more deeply. To earn a cab license in London, drivers must master every one of the city’s 25,000 streets and thousands of landmarks. Brain scans showed that their navigation centers expanded, as though the city’s maze of streets had been inscribed into their neural tissue. The longer they drove, the larger this internal map became [2].

Experience reshapes the brain’s structure, sometimes within weeks, sometimes across years. But for those changes to take root, the right chemistry has to be in place.

Exercise, for instance, has been shown to enhance learning and memory through elevations in specific growth factors in the brain, as well as neurotransmitters that prime circuits for adaptation [3]. This is how exercise drives neuroplasticity. Without that chemical support, the benefits of experience fail to take hold [4].

At the cellular level, plasticity plays out at synapses — the junctions where neurons exchange signals. Whether a connection strengthens or weakens depends on the chemistry at those sites. Among the many molecules that influence this process, magnesium holds a strategic position here. It sits at the heart of the receptors that decide which signals are worth strengthening, and it helps tune the growth factors that tell neurons when to build.

The Gatekeeper: Magnesium at NMDA Receptors

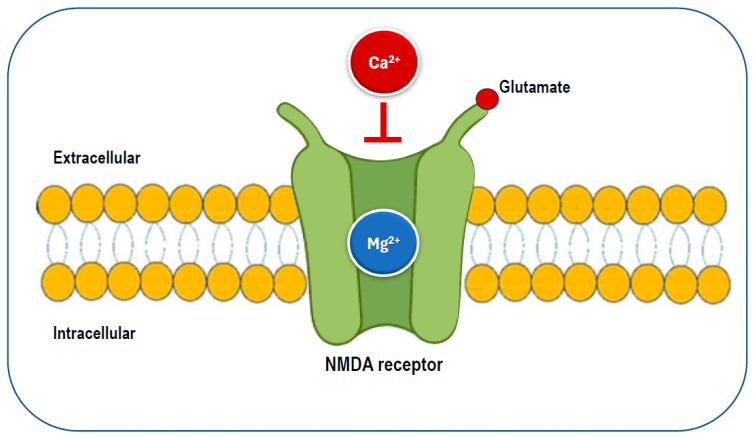

One of the most important of these synaptic receptors is the NMDA receptor, a molecular doorway that responds to glutamate, a neuron’s primary “go” signal. When it opens, calcium rushes in — the spark that tells a neuron, “this connection matters, strengthen it.” This is the ignition of long-term potentiation, the process that underlies memory and learning [5]. In other words, NMDA receptors are the gates through which experience is etched into the brain.

But that gate can’t just be left swinging open. Without regulation, calcium would slip in during random background chatter, strengthening noise instead of meaning. It would be like highlighting every line in a book — nothing stands out.

Here is where magnesium steps in as the gatekeeper. At rest, it sits in the NMDA channel like a bar across a doorway, blocking calcium’s entry. The block lifts only when two conditions are met at the same time: the receptor is activated by glutamate and the surrounding neuron is electrically active [6]. That coincidence enforces a classic principle of neuroscience: neurons that fire together, wire together [7].

By holding the gate shut against stray signals and opening only when timing and coordination align, magnesium ensures the brain strengthens meaningful patterns while filtering out background noise [5].

Magnesium acts as a selective filter for NMDA receptors, blocking calcium until meaningful activity occurs. Image reproduced from L.J. Dominguez, N. Veronese, S. Sabico, N.M. Al-Daghri, M. Barbagallo, Nutrients 17 (2025) 725. CC BY 4.0

The Growth Signal: Magnesium and BDNF

Filtering static is only half the job. Once the right signals make it through, the brain still needs instructions to build on them.

That signal comes from BDNF — brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Often described as the brain’s “fertilizer,” BDNF tells neurons when to sprout new branches and when to reinforce existing ones. It is how experience leaves a lasting trace, making BDNF central to learning, memory, and adaptability [8].

Magnesium appears to amplify this growth signal. In one experiment, rats given a form of magnesium that could cross into the brain showed a surge in BDNF in the hippocampus, the brain’s memory hub. Synapses multiplied, and cognition improved: the rodents ran mazes faster, remembered object locations longer, and could even reconstruct memories from partial hints [9].

How does magnesium achieve this? The mechanism can be traced back to the NMDA receptors. At baseline, magnesium guards these gates, blocking random calcium leaks. When magnesium levels rise suddenly, that block is even stronger — less calcium slips through at rest.

But when levels stay elevated over time, the brain adapts. Neurons add more of a growth-friendly receptor subunit (NR2B), so that background noise stays quiet while genuine signals come through louder and longer. That extended spark activates molecular amplifiers like CaMKII and CREB, which in turn switch on genes for BDNF — enriching synaptic networks and equipping the brain to learn and adapt [9].

Meanwhile, when magnesium levels fall short, the opposite picture emerges. In another experiment, mice that were fed a magnesium-restricted diet showed a clear drop in brain magnesium, accompanied by poorer performance in behavioral tests used to gauge plasticity [10].

So magnesium guards the gateway of learning, but it also helps ensure that once the door is open, the brain has the fertilizer it needs for growth.

But growth only flourishes in the right environment. And one of the most profound threats to that environment is stress.

The Stress Buffer: Magnesium and the HPA Axis

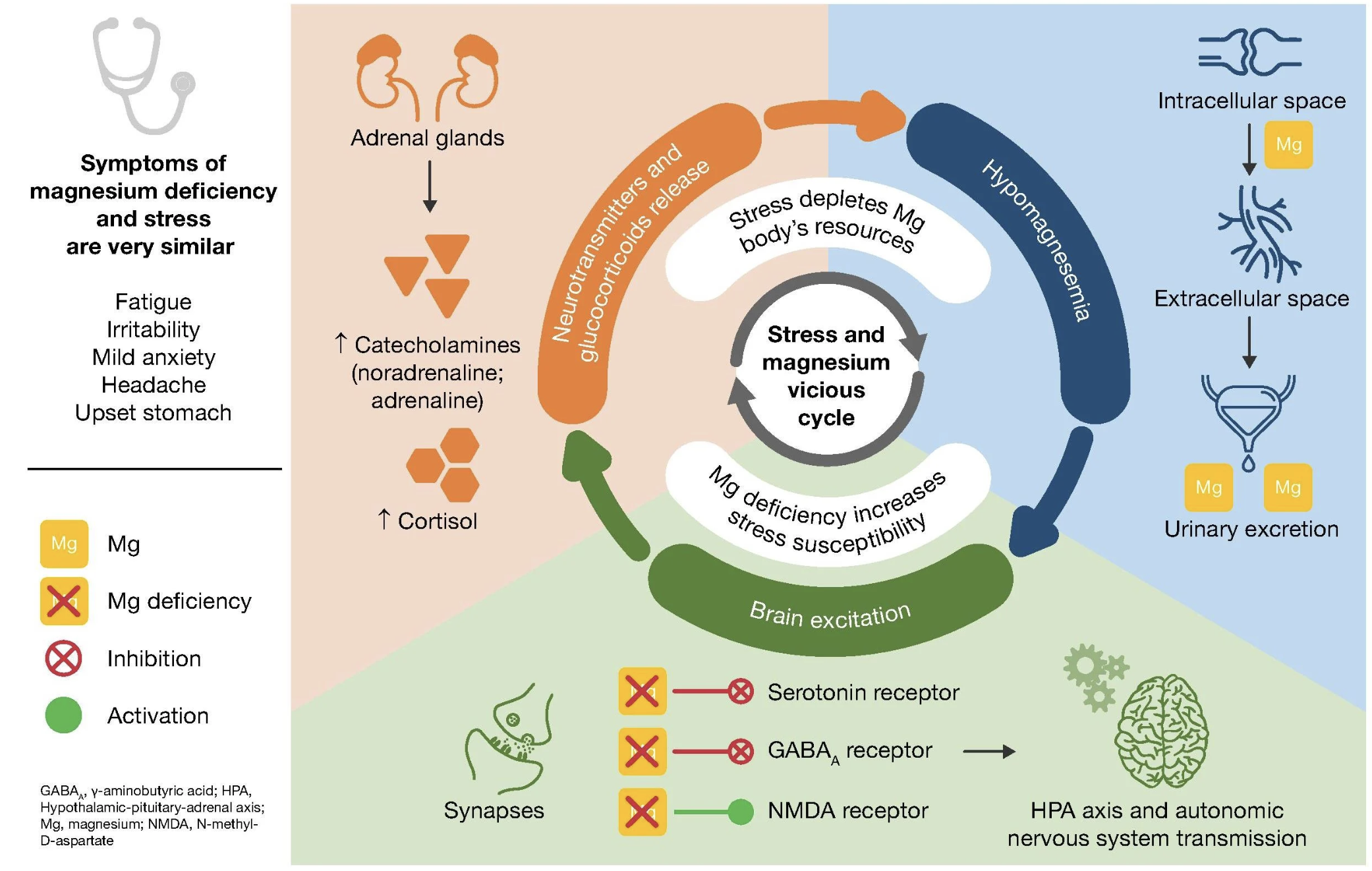

Stress hormones are woven tightly into the machinery of memory, which is why the brain feels their impact so profoundly.

The hippocampus is especially vulnerable because it is saturated with receptors for cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone [11]. In short bursts, activation of these receptors is adaptive. This is why we remember stressful events so vividly. But when cortisol stays elevated, the very system that once stamped in important memories instead begins to destabilize the circuits of plasticity [12].

One way this unfolds is through glutamate, the brain’s main excitatory messenger. Cortisol drives neurons to release more of it, which in moderation helps encode experience. But when cortisol is elevated for too long, glutamate floods the synapse and pushes NMDA receptors wide open [13]. Calcium pours uncontrollably into hippocampal neurons, well beyond the threshold for healthy long-term potentiation [14]. Instead of strengthening select connections, neurons are swamped: dendrites retract, synapses weaken, and memory circuits fray [15].

At the same time, stress dulls the brain’s braking system. Normally, GABA(A) receptors open to let inhibitory signals flow in, slowing excess activity. But cortisol and its metabolites alter how these receptors are assembled and how they function. Under pressure, the brakes slip: instead of calming circuits, GABA signaling can paradoxically add fuel to them [16].

The net result is a circuit that’s noisy, unstable, and unable to focus plasticity where it matters.

Over time, this wear on hippocampal circuits weakens the feedback loop that normally reins in cortisol through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. The stress thermostat breaks [17]. Cortisol spikes even higher, BDNF levels fall, and the brain itself shrinks [12,18].

Over time, this cumulative toll alters both the structure and function of the brain. Longitudinal research has shown that people with years of elevated cortisol exposure have hippocampi about 14% smaller than their peers, accompanied by measurable memory impairments [19].

Magnesium helps buffer this cascade, acting like a shock absorber for the stress system.*

At NMDA receptors, it sits in the channel, blocking excess calcium from rushing in. And at GABA(A) receptors, it makes the brakes more responsive, so calming signals are more likely to get through, even under duress [20,21].*

In effect, magnesium steadies both the accelerator and the brakes, keeping circuits active enough to learn but not so overdriven that stress chemistry erodes them. With feedback to the HPA axis preserved, cortisol can return to baseline, and stress can pass through rather than being carved into the brain [22].*

However, this resilience depends on having enough magnesium to begin with. And that’s where the modern picture starts to look quite bleak.*

Stress chemistry in motion. Rising cortisol shifts neurotransmitter balance — ramping up glutamate, blunting GABA(A), and lowering magnesium — a combination that amplifies neural noise and makes hippocampal circuits more vulnerable to overload. Reproduced from G. Pickering, A. Mazur, M. Trousselard, P. Bienkowski, N. Yaltsewa, M. Amessou, L. Noah, E. Pouteau, Nutrients 12 (2020) 3672. CC BY 4.0

The Modern Magnesium Problem

Magnesium shortfall isn’t rare. It’s arguably the norm.

National survey data show that more than half of U.S. adults fail to consume enough magnesium to meet even the baseline levels nutrition experts consider adequate [23].

Why is it so hard to get enough? Part of the answer lies in agriculture. Since the mid-20th century, fertilizers rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium have pushed yields higher but left magnesium behind [24]. Over time, soils have thinned of the mineral, and so have the crops grown in them.

But most of the population-level decline has come from processing. Magnesium is concentrated in the outer layers of grains and in the germ — the very parts that are subtracted when wheat is milled into white flour or rice is polished.

These losses are stark: whole wheat flour contains about 120 mg of magnesium per 100 g, while refined flour has only 20 mg. White rice falls from 108 mg to just 7 mg, and cornmeal from 93 mg down to 18 mg. This adds up to an 80% loss across common staple grains [25].

Add in the rise of heavily processed foods that are already low in magnesium, and the shortfall becomes structural. The foods we rely on most have been stripped of the mineral, while beans, nuts, and greens — once staple sources — have been pushed to the margins.

And this gap may show up in the brain.

Magnesium and Brain Health: What Research Shows

A recent UK Biobank study offered a sobering window into the impact of magnesium on the central nervous system [26]. About 6,000 middle-aged adults tracked their diets for 16 months, while MRI scans measured the size of key brain regions and looked for white matter lesions — the tiny scars that accumulate with age and chip away at cognitive performance.

The hippocampus stood out in the brain imaging. In participants with higher magnesium intake, it was measurably larger — nearly half a percent bigger — compared to peers who were closer to the average intake of magnesium.

That might sound modest, but it’s equivalent to preserving about a year of normal brain aging. At the other end of the spectrum, people with low intake had hippocampi that were 2–3% smaller, along with more white matter damage. The researchers estimated that a 41% increase in daily magnesium intake could translate into significantly better brain health, especially as people get older.*

But here's the kicker: the brain benefits in this study didn’t appear at the RDA. They showed up at levels well above it. The group with the largest hippocampi was averaging around 550 mg per day. That’s 30–70% higher than current guidelines, and far exceeding what most people actually consume.

In fact, that level of intake looks less like today’s “normal,” and far more like the higher magnesium diets our ancestors evolved on.

Ancestral Magnesium and Brain Plasticity

Anthropological reconstructions suggest our hunter–gatherer ancestors consumed 600 to 1200 milligrams of magnesium daily — two to three times more than the modern average, and nearly triple today’s RDA [27].

The physiological systems that regulate magnesium were shaped in an environment of abundance, which suggests that today’s “normal” may actually be low by evolutionary standards. Modern diets supply enough to ward off deficiency, but not necessarily the levels that best sustain neuroplasticity and long-term health.*

But magnesium was never just about abundance.

In nature, it always arrived with company: dissolved in mineral-rich seawater, or bound in plants alongside dozens of trace elements. Our biology evolved in that context, accustomed to a steady supply of magnesium appearing in concert with other minerals.

Once inside the body, context matters as well. Different forms of magnesium show different affinities: some preferentially raise blood or muscle levels, while others are more effective at crossing into the brain. For instance, magnesium acetyl taurate is one of the few shown to consistently elevate brain magnesium, making it especially relevant for neuroplasticity [28,29]. But it does little for muscle — a role other forms fill more effectively.*

That’s why Qualia Magnesium+ was designed with ten complementary forms of magnesium. Some, like Aquamin®, mirror the mineral diversity of nature. Others, like magnesium acetyl taurate, ensure magnesium reliably reaches the brain. Still others are better suited to building reserves in muscle and other tissues. Layered together, they recreate something closer to what our physiology evolved to expect — the context in which magnesium best supports both whole-body health as well as the brain’s capacity to adapt.*

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

References

[1] B. Draganski, C. Gaser, V. Busch, G. Schuierer, U. Bogdahn, A. May, Nature 427 (2004) 311–312.

[2] E.A. Maguire, D.G. Gadian, I.S. Johnsrude, C.D. Good, J. Ashburner, R.S. Frackowiak, C.D. Frith, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (2000) 4398–4403.

[3] B. Winter, C. Breitenstein, F.C. Mooren, K. Voelker, M. Fobker, A. Lechtermann, K. Krueger, A. Fromme, C. Korsukewitz, A. Floel, S. Knecht, Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 87 (2007) 597–609.

[4] S. Vaynman, Z. Ying, F. Gomez-Pinilla, Eur. J. Neurosci. 20 (2004) 2580–2590.

[5] P. Paoletti, C. Bellone, Q. Zhou, Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 (2013) 383–400.

[6] J.P. Ruppersberg, E. v. Kitzing, R. Schoepfer, Semin. Neurosci. 6 (1994) 87–96.

[7] Y. Munakata, J. Pfaffly, Dev. Sci. 7 (2004) 141–148.

[8] M. Miranda, J.F. Morici, M.B. Zanoni, P. Bekinschtein, Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13 (2019) 363.

[9] I. Slutsky, N. Abumaria, L.J. Wu, C. Huang, L. Zhang, B. Li, X. Zhao, A. Govindarajan, M.G. Zhao, M. Zhuo, S. Tonegawa, G. Liu, Neuron 65 (2010) 165–177.

[10] N. Whittle, L. Li, W.Q. Chen, J.W. Yang, S.B. Sartori, G. Lubec, N. Singewald, Amino Acids 40 (2011) 1231–1248.

[11] S.J. Lupien, F. Maheu, M. Tu, A. Fiocco, T.E. Schramek, Brain Cogn. 65 (2007) 209–237.

[12] S.J. Lupien, R.P. Juster, C. Raymond, M.F. Marin, Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49 (2018) 91–105.

[13] D.M. Osborne, J. Pearson-Leary, E.C. McNay, Front. Neurosci. 9 (2015) 164.

[14] B.S. McEwen, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 583 (2008) 174–185.

[15] D.W. Choi, J. Neurobiol. 23 (1992) 1261–1276.

[16] I. Mody, J. Maguire, Front. Cell. Neurosci. 6 (2012) 4.

[17] J.B. Kuzmiski, V. Marty, D.V. Baimoukhametova, J.S. Bains, Nat. Neurosci. 13 (2010) 1257–1264.

[18] E.R. de Kloet, Neurosci. Appl. 3 (2024) 104047.

[19] S.J. Lupien, M. de Leon, S. de Santi, A. Convit, C. Tarshish, N.P. Nair, M. Thakur, B.S. McEwen, R.L. Hauger, M.J. Meaney, Nat. Neurosci. 1 (1998) 69–73.

[20] E. Poleszak, Pharmacol. Rep. 60 (2008) 483–489.

[21] C. Gottesmann, Neuroscience 111 (2002) 231–239.

[22] B.S. McEwen, P.J. Gianaros, Annu. Rev. Med. 62 (2011) 431–445.

[23] T.C. Wallace, M. McBurney, V.L. Fulgoni III, J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 33 (2014) 94–102.

[24] W. Guo, H. Nazim, Z. Liang, D. Yang, Crop J. 4 (2016) 83–91.

[25] R. Cazzola, M. Della Porta, M. Manoni, S. Iotti, L. Pinotti, J.A. Maier, Heliyon 6 (2020) e05390.

[26] K. Alateeq, E.I. Walsh, N. Cherbuin, Eur. J. Nutr. 62 (2023) 2039–2051.

[27] S.B. Eaton, S.B. Eaton III, Eur. J. Nutr. 39 (2000) 67–70.

[28] M. Ates, S. Kizildag, O. Yuksel, F. Hosgorler, Z. Yuce, G. Guvendi, S. Kandis, A. Karakilic, B. Koc, N. Uysal, Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 192 (2019) 244–251.

[29] N. Uysal, S. Kizildag, Z. Yuce, G. Guvendi, S. Kandis, B. Koc, A. Karakilic, U.M. Camsari, M. Ates, Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 187 (2019) 128–136.

Written by

Written by