Stem cell exhaustion is the gradual loss of regenerative capacity as stem cells — and the signals that guide them — age.

On the surface, this might sound like a simple depletion curve: a steady dwindling of the body’s supply of regenerative cells.

But the biology of stem cell exhaustion is far more complicated.

Some stem cell pools really do shrink. In human skeletal muscle, the fast-twitch–maintaining muscle satellite cells decline by nearly 50% from youth to late life [1].

Other tissues show the opposite pattern. The pool gets bigger, but the cells themselves are less effective.

The bone marrow is a classic example. Aging mice can accumulate nearly 9 times as many hematopoietic stem cells, yet each cell’s regenerative capacity can fall 3-fold [2].

Stem cell exhaustion, in other words, isn’t a single failure. It’s a convergence: intrinsic damage slowing the cell from within, inflammatory noise distorting its cues, and a microenvironment that loses architectural precision.

And you don’t need a bone marrow biopsy to see it. Stem cell exhaustion plays out visibly in muscle, skin, and hair long before deeper organs declare their age.

In this article, we’ll examine what drives stem cell exhaustion, how it emerges across different tissues, and why these fast-turnover systems reveal so much about the biology of aging.

What Causes Stem Cell Exhaustion?

Stem cell exhaustion arises from two forces aging in parallel: the stem cell itself and the environment that guides it.

Intrinsic Aging: When the Stem Cell Itself Slows Down

Stem cells are long-lived, but they’re not immune to time. Each year adds marks to their internal ledger: DNA breaks that take longer to repair, telomeres edging toward critical length, mitochondria producing more oxidative stress and less ATP, and epigenetic patterns drifting like a photocopy of a photocopy [3].

None of these changes destroy the cell outright. Instead, they push it toward caution. And caution carries a price: every hesitation slows tissue renewal.

Extrinsic Aging: When the Stem Cell’s Microenvironment Breaks Down

Stem cells live inside an informational landscape. Cytokines, growth factors, and molecular gradients tell them when to rest, divide, or differentiate. With aging, that landscape degrades. Signals become harder to interpret, like instructions transmitted through a malfunctioning PA system [4].

A now-famous experiment shows just how critical that microenvironment is [5].

When researchers connected the bloodstream of a young mouse and an old one, the old mouse’s tissues behaved as if their clocks had been turned back. Injured muscles regenerated almost like the young’s, new fibers forming at roughly double their usual rate. The liver’s regenerative output jumped several-fold.

But this wasn’t because youthful stem cells crossed over and took the job. Almost none did. The old cells responded differently because the signals around them had changed.

Stem cell exhaustion, then, isn’t just intrinsic wear-and-tear. It’s what happens when the informational environment loses fidelity.

The Stem Cell Niche: How Microenvironments Shape Regeneration

Adult stem cells don’t live in isolation. They occupy tiny structured microenvironments — stem cell niches — that keep their identity stable and their decisions precise. In youth, those cues are crisp. The neighborhood is well lit and every molecule knows its job.

With age, the neighborhood goes downhill [6]. Senescent cells (aka zombie cells; the biological equivalent of long-term squatters) start shouting contradictory instructions. The extracellular matrix stiffens and warps like an old sidewalk. Even perfectly competent stem cells can misfire when the zip code goes feral.

In other words, stem cell exhaustion isn’t always the stem cell wearing out. Sometimes the neighborhood falls apart first.

And you can actually watch a niche fall apart in real time — on your own head.

Stem Cell Niche Breakdown in Real Time: Why Hair Turns Gray

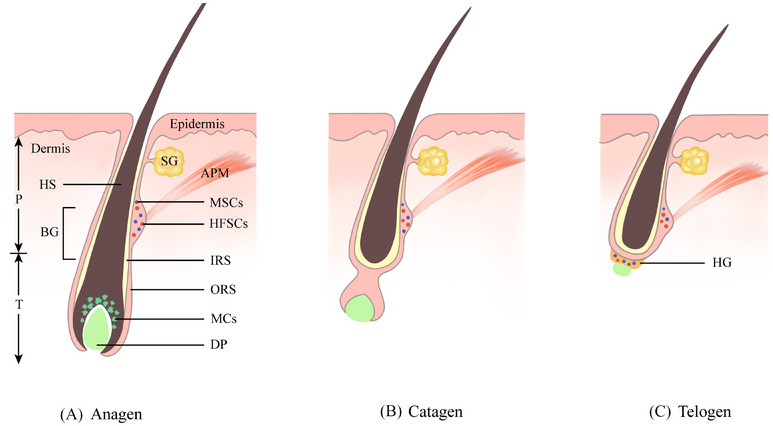

Each hair follicle houses a small team of melanocyte stem cells, the workers responsible for producing pigment.

They reside in a niche called the bulge. When a new hair cycle starts, they migrate to the hair germ, where local signals push them to become pigment-producing melanocytes. Finally, they travel to the hair matrix, where mature melanocytes inject pigment into the growing hair [7].

Hair follicle cycle and melanocyte stem cell behavior. During anagen, melanocyte stem cells in the bulge activate and migrate downward to form pigment-producing melanocytes. In catagen, mature melanocytes are lost as the follicle regresses, while stem cells return to quiescence. During telogen, these stem cells remain dormant in the bulge and hair germ until the next growth phase. Image reproduced from L. Huang, Y. Zuo, S. Li, C. Li, Clin. Transl. Med. 14 (2024) e1720. CC BY 4.0

This commute is how hair stays pigmented for decades, but it only works if the follicle’s internal geography stays intact. And with age, it doesn’t [8].

The once-clear pathways between regions narrow and blur. Gradients that acted like molecular traffic lights fade. The structural map that melanocyte stem cells follow becomes unreliable.

As a result, eventually, they get stuck. Literally stuck.

Instead of returning to the bulge or reaching the germ, aging melanocyte stem cells become stranded in the outer root sheath, drifting into a half-committed identity they can’t escape. When enough cells are marooned, pigment production collapses, and the next hair grows in gray [9].

Gray hair is niche failure made visible, a reminder that capable stem cells can fail when the structure around them loses coherence.

Inflammation and Stem Cell Exhaustion

Stem cells depend on contrast — long stretches of quiet punctuated by clear bursts of instruction.

Aging erases that contrast. The body slides into a low-grade inflammatory hum. Senescent cells emit SASP. The immune system slots into an “always-on” mode known as inflammaging [10].

Instead of receiving clear instructions, stem cells are hit with static [11]. Signals arrive at the wrong time or the wrong amplitude. This makes stem cells activate too slowly, differentiate prematurely, or stall in limbo. In effect, they are trying to interpret messages where a fire alarm won’t shut up.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in muscle, a tissue that lives and dies by the sharpness of these cues.

How Inflammation Shapes Muscle Repair

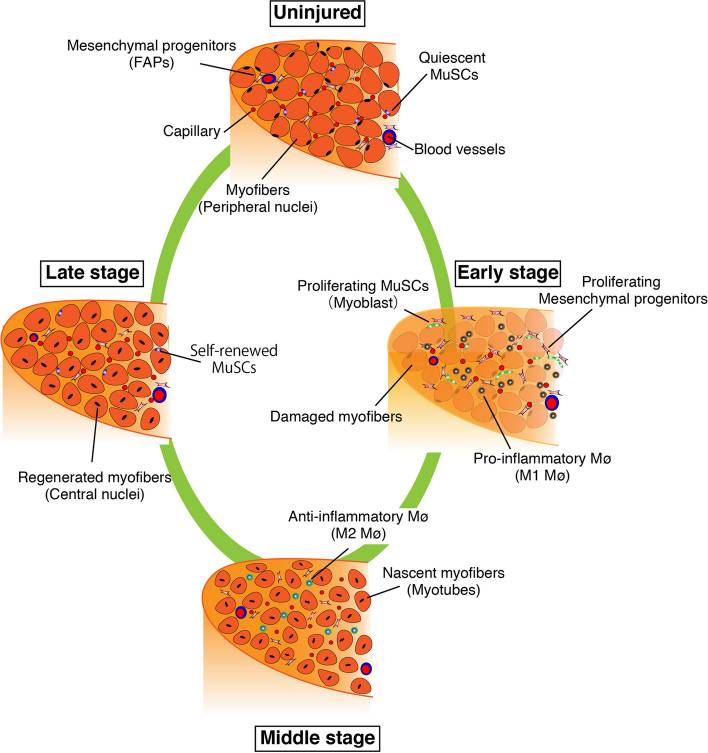

Every hard workout leaves behind a microscopic battlefield: Z-disks unraveled, proteins frayed at the edges, and mitochondria pushed to their limits [12].

It’s destruction with a purpose.

Muscle responds with a tightly timed inflammatory burst [13]. Cytokines spike just long enough after exercise to tell muscle satellite cells: “Wake up. Repair this.”

Stages of skeletal muscle regeneration. Damage after training triggers an early inflammatory phase where macrophages clear debris and muscle satellite cells begin proliferating. As inflammation resolves, anti-inflammatory macrophages support differentiation and the formation of nascent myofibers, which mature into regenerated muscle in the late stage. Image reproduced from S. Fukada, T. Higashimoto, A. Kaneshige, Skelet. Muscle 12 (2022) 17. CC BY 4.0

That spike can be loud. The cytokine IL-6 can jump over 100-fold during prolonged exercise — one of the largest acute cytokine responses in human physiology [14].

This pulse of inflammation is how the body jerks satellite cells out of quiescence [15]. It’s the biochemical equivalent of kicking the door in. And it is not optional.

In one study, a long run expanded the satellite cell pool by ~27% [16]. But when the athletes took an NSAID for a week, that expansion was abolished. As the authors put it: “Anti-inflammatory drugs attenuate the exercise-induced increase in satellite cell number.”

In youth, this choreography is clean. With age, the spike has to fight its way through background noise.

How Inflammation Disrupts Muscle Stem Cells With Age

Later in life, the problem isn’t that the post-exercise spike disappears. It’s that the baseline creeps upward until contrast evaporates. Inflammation becomes more like biochemical tinnitus.

Cytokines that were once ephemeral now linger at 2–4× their youthful baseline [17]. Macrophages hover after their cleanup shift is done. The whole system develops the timing of a laggy Zoom call. As a result, activation cues arrive early, or late, or without enough amplitude to matter.

And you don’t need a microscope to see the toll. Muscle strength drifts downward by roughly 12–15% per decade after 50 [18]. Muscle mass can fall by nearly 50% by age 70 [19]. This is the imprint of a repair system that has lost its clarity.

Cellular Damage: DNA, Telomeres, and the Slowing of Stem Cell Renewal

Every long-lived stem cell keeps a private ledger of what it has endured. DNA breaks patched imperfectly, telomeres worn down to the nub, oxidative nicks scattered across the genome [20].

In youth, the ledger is almost blank. But with age, the entries pile up.

A regular cell can afford a mistake. A stem cell can’t. Its descendants will populate the tissue for years. So when DNA damage lingers or a telomere approaches its limit, stem cells step on the brakes. They stretch the pause between divisions and run extra rounds of p53 surveillance [21].

As more and more stem cells adopt this defensive stance, tissues begin to feel the cumulative drag.

Most organs conceal this slowdown deep inside. The skin does not.

Skin: Where Stem Cell Exhaustion Is Revealed

Skin is one place where stem cell exhaustion can’t hide. It’s staring back at you in the mirror.

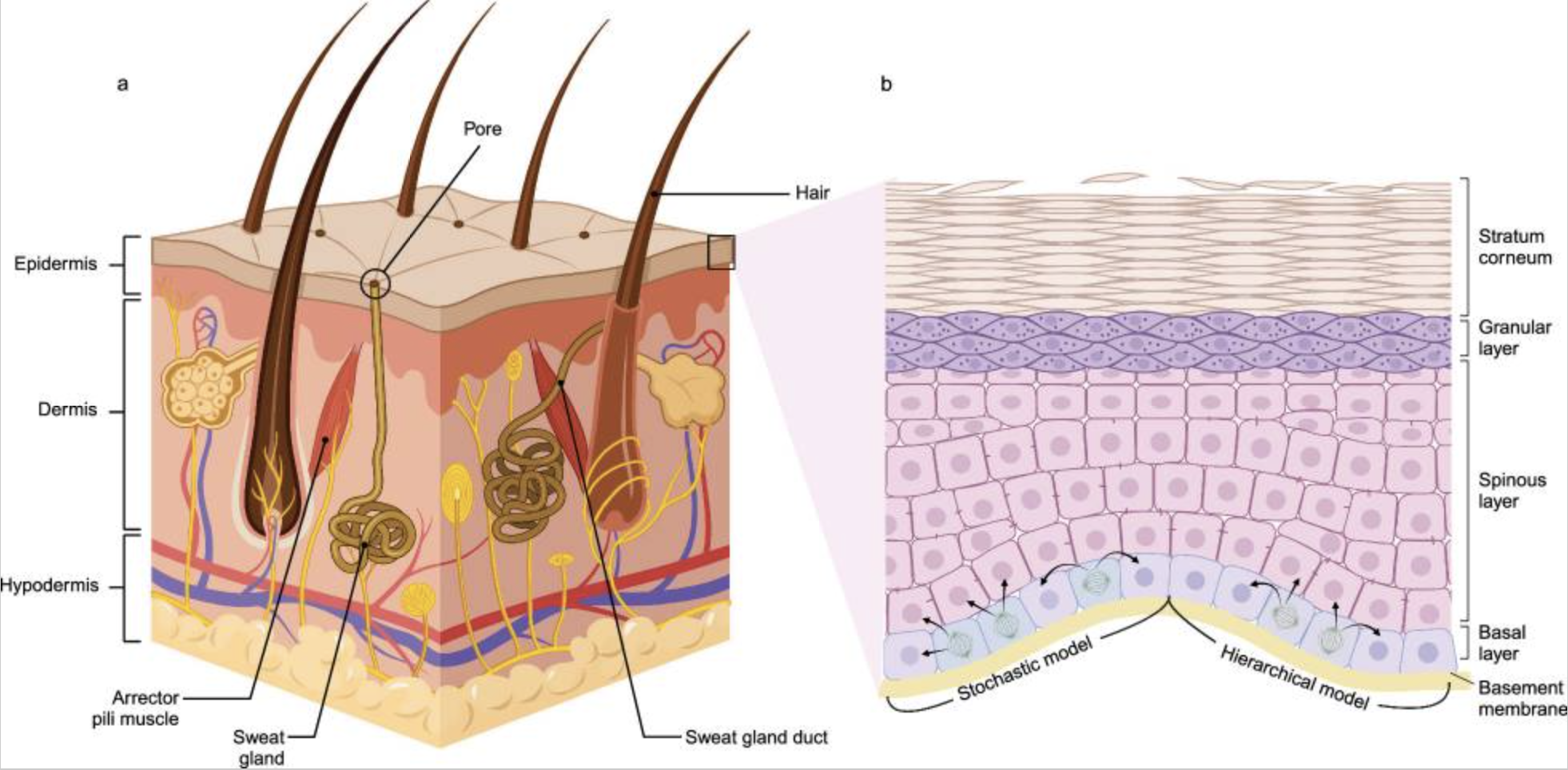

The epidermis relies on a small population of basal stem cells to continuously rebuild its layers [22]. In youth, the surface refreshes every few weeks. That’s why young skin looks so bright — it’s wearing a fresh coat of paint.

Overview of skin anatomy and basal stem cell behavior. Left: major layers of the skin and associated appendages. Right: how basal-layer stem and progenitor cells populate the epidermis through different differentiation models. Image reproduced from X. Tang, J. Wang, J. Chen, W. Liu, P. Qiao, H. Quan, Z. Li, E. Dang, G. Wang, S. Shao, J. Transl. Med. 22 (2024) 779. CC BY 4.0

Overview of skin anatomy and basal stem cell behavior. Left: major layers of the skin and associated appendages. Right: how basal-layer stem and progenitor cells populate the epidermis through different differentiation models. Image reproduced from X. Tang, J. Wang, J. Chen, W. Liu, P. Qiao, H. Quan, Z. Li, E. Dang, G. Wang, S. Shao, J. Transl. Med. 22 (2024) 779. CC BY 4.0

That speed holds as long as the stem cells feel safe dividing. But epidermal stem cells endure more wear-and-tear than nearly any other cell. Oxidative stress, replication errors, and the relentless attrition of decades of turnover. Each unrepaired break flips on p53 and p21 — the cellular equivalent of a yellow light — nudging stem cells toward caution [23].

Eventually, the stem cell starts behaving like someone who has been rear-ended one too many times: slow to accelerate and not eager to take chances.

And then there’s sunlight — the great accelerant.

Within minutes of UV exposure, the skin’s DNA sprouts lesions so badly kinked that the replication machinery stalls. Most lesions do get repaired. But these stem cells hang around for decades, so whatever doesn’t get fixed… stays. And accumulates. Meanwhile, telomeres shorten with every cycle, telling the cell that division is a risky bet.

When millions of basal stem cells adopt that cautious stance, the entire renewal cycle slows [24]. In young adults, the epidermis turns over every 20–30 days. By later life, it can drag past 60 days [25].

The places that take the biggest beating — sun-exposed zones — show it most clearly.

Repeated UV exposure results in measurable reductions in stem/progenitor cell markers. Visually, this looks like a dulled surface, fine lines that deepen as turnover slows, and pores that appear larger because the scaffolding beneath them isn’t rebuilt as quickly [26].

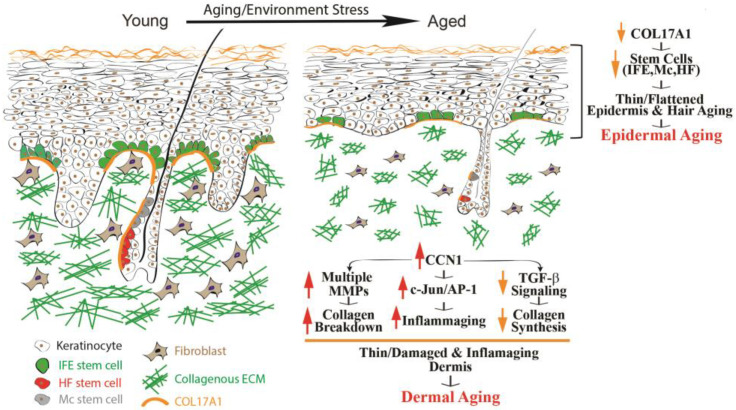

How aging alters the epidermis, dermis, and their stem cell niches. With age, epidermal stem cells lose structural support and the layer thins, while the dermis shows collagen breakdown and rising inflammatory signals. Together these changes weaken the skin’s regenerative capacity and contribute to visible aging. Image reproduced from T. Quan, Biomolecules 13 (2023) 1614. CC BY 4.0.

How aging alters the epidermis, dermis, and their stem cell niches. With age, epidermal stem cells lose structural support and the layer thins, while the dermis shows collagen breakdown and rising inflammatory signals. Together these changes weaken the skin’s regenerative capacity and contribute to visible aging. Image reproduced from T. Quan, Biomolecules 13 (2023) 1614. CC BY 4.0.

And these changes aren’t merely cosmetic.

In a controlled human wound model, healthy older adults needed nearly two extra days to re-epithelialize the same small cut — roughly a 25% slowdown in regeneration [27].

This is the surface-level signature of stem cells choosing caution over speed. Cells that can still divide, but decide the gamble isn’t worth it.

Can Stem Cell Exhaustion Be Slowed? What Science Suggests

Stem cell exhaustion appears among the original Hallmarks of Aging [28].

But in practice it behaves less like a peer and more like a final readout — the point where upstream hallmarks translate into lost adaptability.

Genomic instability forces stem cells to divide with extra caution.

Epigenetic drift blurs their sense of identity.

Telomere attrition limits how many reliable daughters they can produce.

Mitochondrial inefficiency slows the metabolic push required for renewal.

Inflammation — amplified by senescent cells leaking SASP — floods the niche with static, obfuscating even the cleanest cues.

Stem cell exhaustion is the convergence of these forces.

The good news is that these pressures are, at least in theory, modifiable.

For skin, topical retinol overrides the defensive hesitation of aging epidermal stem cells, boosting proliferation and accelerating turnover. These vitamin A derivatives can dramatically shorten epidermal renewal time, restoring a more youthful tempo of replacement [29].

Gray hair is…trickier. The issue isn’t pigment production — the melanocytes still work — but navigational failure inside the follicle. Early work is beginning to explore ways to restore the “road map” that melanocyte stem cells need to complete their commute [30].

Muscle may be the most tractable of all. In lifelong athletes, decades of training preserves the high-contrast signaling pattern that satellite cells rely on. Their resting IL-6 levels run lower than sedentary age-matched peers, and their acute inflammatory response to resistance exercise mirrors that of 25-year-olds [31].

Taken together, these examples hint that supporting stem cells isn’t necessarily about “fixing” them. It’s about reducing noise, restoring structure, and giving these long-lived cells an environment where caution isn’t their only option. This is the same logic behind using Qualia Stem Cell for renewal as a periodic support tool—to help reduce that background noise and gently reinforce the signals that keep regeneration online as we age.*

Stem cell supplements can help. Qualia Stem Cell was created with that same systems-level insight: that long-term stem cell capacity depends on the integrity of their signaling environment.*

Its 4-day pulse-based protocol was built to echo the way stem cells naturally respond to intermittent cues, offering support without the relentless pressure that can erode long-lived systems over time.*

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.

References

[1] L.B. Verdijk, T. Snijders, M. Drost, T. Delhaas, F. Kadi, L.J. van Loon, Age (Dordr.) 36 (2014) 545–547.

[2] S.M. Chambers, C.A. Shaw, C. Gatza, C.J. Fisk, L.A. Donehower, M.A. Goodell, PLoS Biol. 5 (2007) e201.

[3] J. Oh, Y.D. Lee, A.J. Wagers, Nat. Med. 20 (2014) 870–880.

[4] R. Farahzadi, B. Valipour, S. Montazersaheb, E. Fathi, Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11 (2023) 1162136.

[5] I.M. Conboy, M.J. Conboy, A.J. Wagers, E.R. Girma, I.L. Weissman, T.A. Rando, Nature 433 (2005) 760–764.

[6] L. Li, T. Xie, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21 (2005) 605–631.

[7] Q. Sun, W. Lee, H. Hu, T. Ogawa, S. De Leon, I. Katehis, C.H. Lim, M. Takeo, M. Cammer, M.M. Taketo, D.L. Gay, S.E. Millar, M. Ito, Nature 616 (2023) 774–782.

[8] E. Steingrímsson, N.G. Copeland, N.A. Jenkins, Cell 121 (2005) 9–12.

[9] X. Zhang, J. Zhu, J. Zhang, H. Zhao, J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 22 (2023) 1720–1723.

[10] H.E. Kunz, I.R. Lanza, Exp. Gerontol. 177 (2023) 112177.

[11] I.M. Conboy, M.J. Conboy, J. Rebo, Aging (Albany NY) 7 (2015) 754–765.

[12] P.M. Clarkson, M.J. Hubal, Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 81 (2002) S52–S69.

[13] J.M. Peake, O. Neubauer, P.A. Della Gatta, K. Nosaka, J. Appl. Physiol. 122 (2017) 559–570.

[14] A. Steensberg, G. van Hall, T. Osada, M. Sacchetti, B. Saltin, B. Klarlund Pedersen, J. Physiol. 529 (2000) 237–242.

[15] B.M. Lapointe, P. Frémont, C.H. Côté, Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 282 (2002) R323–R329.

[16] A.L. Mackey, M. Kjaer, S. Dandanell, K.H. Mikkelsen, L. Holm, S. Døssing, F. Kadi, S.O. Koskinen, C.H. Jensen, H.D. Schrøder, H. Langberg, J. Appl. Physiol. 103 (2007) 425–431.

[17] H. Brüünsgaard, B.K. Pedersen, Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 23 (2003) 15–39.

[18] E. Volpi, R. Nazemi, S. Fujita, Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 7 (2004) 405–410.

[19] K. Nowakowska-Lipiec, H. Zadoń, R. Michnik, A. Nawrat-Szołtysik, J. Clin. Med. 14 (2025) 7276.

[20] T. McNeely, M. Leone, H. Yanai, I. Beerman, Hum. Genet. 139 (2020) 309–331.

[21] A.S. Ahmed, M.H. Sheng, S. Wasnik, D.J. Baylink, K.W. Lau, World J. Exp. Med. 7 (2017) 1–10.

[22] M.I. Koster, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1170 (2009) 7–10.

[23] U. Panich, G. Sittithumcharee, N. Rathviboon, S. Jirawatnotai, Stem Cells Int. 2016 (2016) 7370642.

[24] K. Maeda, Cosmetics 4 (2017) 47.

[25] L. Baumann, J. Pathol. 211 (2007) 241–251.

[26] S. Iriyama, M. Yasuda, S. Nishikawa, E. Takai, J. Hosoi, S. Amano, Sci. Rep. 10 (2020) 12592.

[27] D.R. Holt, S.J. Kirk, M.C. Regan, M. Hurson, W.J. Lindblad, A. Barbul, Surgery 112 (1992) 293–298.

[28] C. López-Otín, M.A. Blasco, L. Partridge, M. Serrano, G. Kroemer, Cell 153 (2013) 1194–1217.

[29] T. Quan, Biomolecules 13 (2023) 1614.

[30] Z. Feng, Y. Qin, G. Jiang, Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19 (2023) 4588–4607.

[31] K.M. Lavin, R.K. Perkins, B. Jemiolo, U. Raue, S.W. Trappe, T.A. Trappe, J. Appl. Physiol. 128 (2020) 87–99.

Written by

Written by